Click to join the conversation with over 500,000 Pentecostal believers and scholars

Click to get our FREE MOBILE APP and stay connected

| PentecostalTheology.com

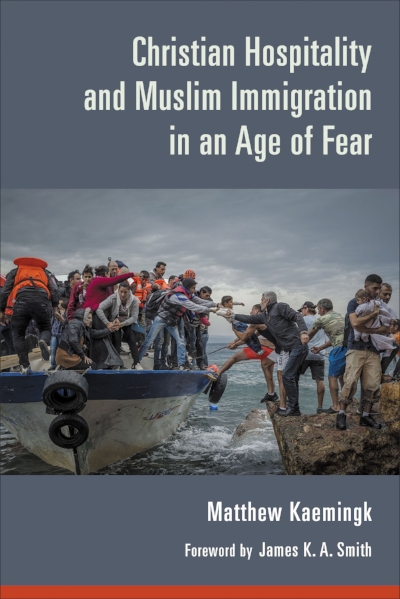

Matthew Kaemingk, Christian Hospitality and Muslim Immigration in an Age of Fear (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2018), 338 pages.

Matthew Kaemingk, Christian Hospitality and Muslim Immigration in an Age of Fear (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2018), 338 pages.

The kind of book Evangelical Christians need to be reading on navigating Christian-Muslim relations today is the kind of book Matthew Kaemingk has written in Christian Hospitality and Muslim Immigration in an Age of Fear. So then, I am beginning this review with a positive recommendation right up front. Please let me explain why.

Matthew Kaemingk is assistant professor of Christian ethics and associate dean at Fuller Theological Seminary. Kaemingk earned his Master of Divinity from Princeton Theological Seminary and holds doctoral degrees in Systematic Theology from the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam and in Christian Ethics from Fuller Theological Seminary. Kaemingk is an ordained minister in the Christian Reformed Church. He presently lives in Houston with his wife Heather and their three sons Calvin, Kees, and Caedmon.

Kaemingk’s research and teaching focus is on Islam and political ethics, faith and the workplace, theology and culture, and Reformed public theology. Thus Christian Hospitality and Muslim Immigration in an Age of Fear comes rather directly out of his primary expertise. And it shows. The Foreword by Jamie Smith, quite the heavy hitter himself and a Charismatic Calvinist on top of that, not only testifies to the credibility of Kaemingk’s work and frames it for readers but helps connect it with Evangelical Reformed readers as well as Pentecostal/Charismatic readers.

Matthew Kaemingk faces several pressing questions head-on. How can diverse people live together? How should Western Christians respond to their new Muslim neighbors? Can Islam and Christianity peacefully coexist? Are there limits to religious freedom and tolerance? How much religious diversity can a single nation withstand? He believes the far left’s unqualified concessions and the far right’s reflex aggressions are both mistaken. Yet he does not simply draw a line down the middle between the two. He proposes another option: “Christian hospitality” or, as he (cover aside) more often puts it, “Christian pluralism”. Yet before prematurely dismissing him at this point readers should note that he does not mean by “pluralism” what may be the first thought which comes to many minds (i.e. he is certainly no John Hick). Kaemingk is firmly committed to the exclusivity of Jesus Christ as the one and only Savior and Lord. He is also firmly committed to loving neighbors—even enemies, if so they be—of other faiths.

How can diverse people live together?

Kaemingk is sure that Christians must respond to the crisis precipitated by the massive increase of Muslim immigration to the West in a specifically Christian manner. He sees theologians such as himself as servants attempting to help facilitate that process. He does not address, important as it is, the question of salvation after death so much as the question of life together before dying. He carefully defines pluralism in terms of culture, structure, and direction in life, and the varied responses Christians can and should make to each. But he does argue for a “Christian pluralist”—one who is personally committed to Christ while being tolerant of and engaged with others—as well suited to navigate the current crises between Christians and Muslims brought on by globalization and immigration.

![* Tested 10 days” Daniel 1:1-21 [1]In the third year…](https://www.pentecostaltheology.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/-Tested-10-days-Daniel-1121-1In-the-third-year-600x360.png)

Most Talked About Today