Click to join the conversation with over 500,000 Pentecostal believers and scholars

Click to get our FREE MOBILE APP and stay connected

| PentecostalTheology.com

Summary

In the article, “Richard Bauckham on Jurgen Moltmann’s Eschatology” in Alister McGrath’s The Christian Theology Reader (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2007), Richard Bauckham contends that one of the most important achievements in Moltmann’s theology is his rehabilitation of eschatology for modern biblical faith. Contrary to Schweitzer, Dodd, Bultmann and other theologians of the modern era who considered biblical eschatology objectionable to contemporary minds unless modified to reflect a more figurative or abstract interpretation, Moltmann asserts that restoring biblical eschatology reinstates the reliability and relevancy of the Christian faith in the modern world. Instead of the church rejecting or retreating from the process of constant and radical change in the modern experience of history, a reorientation of faith towards the future compels the church to dynamically reconnect with the contemporary world and redirect it towards a future kingdom. For Moltmann, the very essence of the gospel is rooted and grounded in eschatological faith and is an empowering factor in transforming the present in the direction of the promised future.

Thoroughly Christological in nature, Moltmann’s understanding of biblical eschatology is centred upon his understanding of the resurrection of Jesus. The resurrection of Jesus is the promise of Christian hope and the eschatological future of all reality. Moltmann sets forth his argument by contextualizing the resurrection of Jesus against the backdrop of Jewish history and theology. Throughout the Old Testament, the God of Israel revealed himself to his people through his promises of future hope. Within this promissory framework, God resurrects the crucified Christ from the dead, enacting the supernatural fulfilment of his divine pledge. The resurrection of Jesus not only demonstrates the certainty of God’s promise of future hope, but also anticipates the resurrection of all the dead, the new creation of all reality, and proclaims the coming of the kingdom of God.

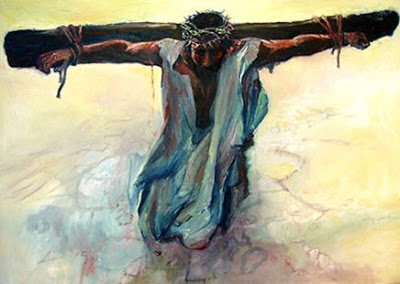

Moreover, this idea of resurrection as promise is further magnified when juxtaposed with Moltmann’s dialectical understanding of the cross and resurrection as contradiction. First, the contradiction of the cross and the resurrection is itself eschatological, contrasting the reality of death and the promise and new life. Though the cross represented death, the resurrection symbolizes life for the dead, righteousness for the unrighteous, and a radically new future. Second, the contradiction of the cross and resurrection are characterized in the identity of Jesus. Jesus did not merely survive the cross; he who was wholly dead has been wholly raised, dramatically illustrating the radical and total transformation of the Son and characterizing the nature of transformation in the eschaton, where the hope of creational resurrection will ultimately be fulfilled.

Thus, for Moltmann, Christian eschatology is hope; hope for a different world, free from all evil, suffering, and death and filled with the presence of God. Completely transcendent of history and the machinations of humanity, this radical change will be completely achieved by God according to his teleology. However, this hope is not without effect on the present. The resurrection of Jesus activated a process in history that moves the world in the direction of future transformation by affecting change in the existing world. This progression of change is, for Moltmann, achieved by the church, who demonstrates to the world that transformation is not only anticipated but is effectual in the contemporary context. Instead of being other-worldly and disengaged from reality or resigned to the inalterability of world affairs, the promise of hope in the eschaton ignites and empowers the church to seek and activate all opportunities to effect change and express the divine nature of resurrection promise to the world. Thus, for the Christian, the eschaton is not only an anticipation of restoration, but is the central motivating factor in viewing the present world as transformable in the direction of the promised hope of resurrection.

Implications

Richard Bauckham states how Moltmann’s eschatology differs from other prominent theologians of the modern age whose liberal theologies have pervaded the church and influenced the pulpit of the twentieth century. Instead of relegating biblical eschatology to the attic of Christian theology, considering its concepts embarrassing to the logicality of modern thinking and irrelevant to contemporary faith, Moltmann resists the theories of his counterparts and restores the biblical concept of future hope. Reviving the notion that there is not only a real future kingdom to come, but the anticipated future kingdom is active in the present world, Moltmann recovers the eschatological significance of Scripture, which for him, seems to represent a corpus that not only speaks to the past and present, but also speaks to the future. Identifying the promise of hope motif as existent in the history of Israel and demonstrated in the resurrection of Jesus, he reveals the biblical trajectory of hope that will ultimately be achieved in the future eschaton. This perspective implies that the Bible is not just a voice of antiquity, but a relevant voice that can speak to the modern Christian about living in the present in light of the anticipation of the consummation of the kingdom of God.

Additionally, Moltmann inexorably ties biblical eschatology to ecclesiology, emphasizing how the promise of future restoration serves as a stimulus for the church to actualize change in the present. Instead of the church perceiving the world to be following a hopeless and unchangeable course, eschatology becomes the central motivating factor and vision of hope to bring the world into alignment with the promised future. Viewing the world as transformable in the direction of the eschaton liberates the church from accommodation to the status quo and sets the church critically against it, enabling it to seek and activate present possibilities that arouse an active expectation and awareness of the eschatological future. Though the church lives in the present world of evil, sin, and suffering, the future kingdom is anticipated, preventing the church from being absorbed by the corrupt conditions and, though suffering the contradiction of present affliction in light of future restoration, the church actively pursues new impulses of change that direct the world towards the future eschaton. Thus for Moltmann, eschatology is intrinsically linked to the mission of the church as the motivating force to actualize change in the contemporary context.

Lastly, Moltmann’s rediscovery of biblical eschatology confronts the community of faith with the challenge of living according to the biblical principles of the approaching kingdom. Recognizing that this present world will be wholly restored in the future, believers are compelled to thoughtfully examine the nature of their relationship to the world and its value systems. Though tempted to be conformed to secular patterns, believers are called to live according to the expectations of the kingdom in anticipation of the ultimate fulfilment of the promised future. Just as Jesus successfully engaged the world without being contaminated by the world and effected change with eschatological motivation, the believing community is also called to avoid being polluted by the world, yet live in the world as agents of change in anticipation of the coming kingdom of God.

Critical Reflection on Jurgen Moltmann’s View of the Suffering of God by William Sloos

Summary

In Jurgen Moltmann’s article, ‘The Crucified God’: God and the Trinity Today in the The Christian Theology Reader, he argues how the cross of Christ demonstrates the suffering of God for the sake of fallen humanity and is essential in understanding the inner relationship between the Father and the Son. He states that through the suffering of the Son on the cross, the Father also experienced suffering, though distinct from the experience of the Son. While the Son suffered the physical pain of the cross and the pain of being abandoned by the Father, the Father suffered because he abandoned his Son. This suffering however, was not like the suffering of created beings, which is associated with their fallen state, but was rather a voluntary suffering whereby God allowed himself to be affected by external influences, specifically his love for fallen humanity. Contrary to Aristotle’s God, who was loved by all but was incapable of loving, the Christian God has the capacity to love and the capacity to suffer for that which he loves.[1] This suffering of both the Father and the Son illustrates how they are of the same substance and, even though they suffered differently, they were united in their suffering for the sake of fallen humanity.

The cross also illustrates the triune nature of God and is, according to Moltmann, the most concise expression of the Christian doctrine of the Trinity. Combating the heresies of the Patripassians who held to a monarchian theology that believes the Father was crucified through the Son, or the Theopaschites, who believe the divine nature of Christ died on the cross, Moltmann emphasizes how both the universality of the Godhead and the distinctiveness of the three persons are present in the atonement. In effect, Moltmann argues that the Trinity must be understood in the context of the cross, which reveals the unity of God in the context of faith, affirming the traditional orthodox doctrine of the nature of God.[2]

Additionally, Moltmann argues that the cross is essentially a divine act involving every member of the Trinity, stating that the Father allowed the Son to sacrifice himself through the Holy Spirit. Pointing to the passage in Romans 8:32 which states, “God did not spare his own Son, but gave him up for us all,” he states that the Father abandons, or “gives up” his Son and is separated from him, and the Son is abandoned, or “given up” by the Father, and this “giving up” is the Holy Spirit. That is, the separation experienced between the Father and the Son occurred through the means of the Holy Spirit. This abandonment and separation at the cross is thus a Trinitarian event, whereby each person of the Trinity directly participates in the salvific design: the Father abandons, the Son is abandoned, and the Spirit is the means of the abandoning, to reconcile human beings back to God.[3]

Critical Reflection

Moltmann’s argument of a suffering God effectively illustrates the love that God has for fallen humanity. If one voluntarily suffers on behalf of something or someone, they must love that something or someone because suffering is a painful experience; one would only choose to suffer if one considered that something or someone worth suffering for, and that is love. As an illustration, if a foreign army is attacking a country and a citizen of that country volunteers to join the army and then suffers in battle defending their country, that citizen must consider their country worth suffering for, and thus, must love their country. In the same way, God, who was under no obligation or compulsion, chose to abandon his Son and suffer the pain of separation because of his love for fallen humanity. In the freedom of his perfect nature, God demonstrated perfect love to an undeserving and fallen humanity.

Within human relationships, if a father chooses to abandon his own son and separate himself from the torment of his son’s suffering, the father either does not love his son, or considers something or someone worth enduring the pain of his actions. Since it is understood from the Scriptures that God is love, he must by his own definition, love his Son. He thus must have considered fallen humanity worth the pain of abandoning the Son he loves to death on a cross. If he considers fallen humanity worth such personal suffering, he must love human beings, and love them with the same love that defines his divine nature.

In addition to loving human beings, his altruistic and selfless act displayed in the atonement also shows that he values human beings. If God values human beings, it is arguable then that he is interested in having a relationship with them, caring for their needs and guiding their lives for all eternity. Why would anyone go through such pain and suffering if they did not intend to pursue a relationship with them afterwards? The cross is therefore, not just a means of providing salvation to fallen humanity, but represents God’s passionate and intimate concern for all people and his unselfish desire to engage in a personal and eternal relationship with each human being.

Implications

If God willingly chose to abandon his Son and experience the pain of separation for his love of fallen humanity, then he must be a God who is worth obeying and worshipping. By his actions displayed at the cross, he has shown human beings that he is a good and loving God and is interested in liberating human beings from sin and its consequences. Thus, it would be reasonable and fitting for those human beings who have received the benefits of the cross through faith to live their lives in a manner that pleases him. Through the acts of obedience and worship, in accordance with the revealed Word of God, human beings can demonstrate their gratefulness to the one who has suffered for their salvation.

Additionally, Molmann’s claim that the cross is the central focus of the Christian faith is very significant for the contemporary church. Among the liberal community of faith or those espousing a social gospel, the cross has lost its significance and simply stands as a symbol of the Easter story, irrelevant to the current cultural context. Conversely, some influential brands of evangelicalism are promoting a prosperity gospel that is contrary to the message of the cross. However, the message of the cross is the gospel, proclaiming the love of God for all people and demonstrating the magnitude to which the Trinity went to rescue fallen humanity. Without the emphasis on the cross of Christ, the nature of God is misunderstood, the value of salvation is diminished, and the church’s message is emptied of its power.

In conclusion, Jurgen Moltmann contends that the cross of Christ is essential in understanding the relationship between the Father and the Son, and how their suffering, though unique, was united in their love for fallen humanity. Additionally, the author illustrates how the triune nature of God is evident in the cross of Christ; God suffered the loss of his Son, the Son suffered the pain of the cross, and the Holy Spirit was the means by which the event was accomplished. In his argument, Moltmann also passionately demonstrates the immense love God has for fallen humanity and his willingness to suffer on their behalf.

Bibliography: McGrath, Alister E., ed. The Christian Theology Reader. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

Most Talked About Today