Click to join the conversation with over 500,000 Pentecostal believers and scholars

Click to get our FREE MOBILE APP and stay connected

| PentecostalTheology.com

William Sloos

Abstract:

Confronting the early Pentecostal movement was dispensationalism, a prevailing fundamentalist theology that conflicted with Pentecostal ecclesiological and eschatological distinctives. Although early Pentecostals concurred with most dispensational teachings, their experience of Spirit-baptism prevented them from accepting two significant dispensationalist tenets: 1) spiritual gifts had ceased following the apostolic period and 2) the church age would end in apostasy. To early Pentecostals, the charismatic gifts were being restored to the church in preparation for a global end-times revival. This difference in ecclesiology and eschatology set the early Pentecostals at odds with the pessimistic nature of dispensational hermeneutics. Having difficulty explaining their charismatic experiences through dispensational language, Pentecostals would turn to the latter rain motif to articulate their emerging distinctives. This article examines the conflict between dispensationalism and early Pentecostalism and explores how early Pentecostals adopted the latter rain motif as an alternative theological framework to articulate their ecclesiological and eschatological distinctives.

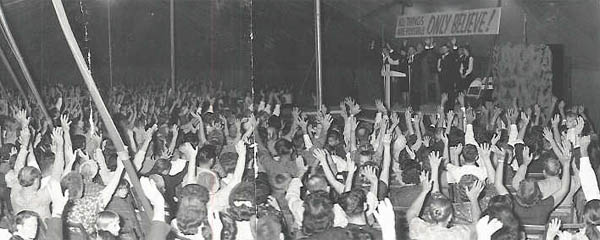

Early Pentecostal Revival Service in America

Introduction

Following the birth of the Pentecostal movement in the early twentieth century, Pentecostals were confronted with dispensationalism, a prevailing fundamentalist theology that conflicted with their emerging ecclesiastical and eschatological distinctives.{C}[1] Developed in the mid-nineteenth century by John Nelson Darby, dispensational theology was a system of interpreting biblical history as a series of successive dispensations culminating in a clearly defined eschatological framework.[2] Although early Pentecostals concurred with most dispensational hermeneutics, their experience of Spirit-baptism prevented them from accepting two significant dispensationalist tenets: 1) the gifts of the Holy Spirit had ceased following the apostolic period and 2) the church age would end in apostasy.[3] Clearly apparent to Pentecostals, the charismatic gifts had not ceased after the apostolic age, but were now being restored to the church through the outpouring of the Holy Spirit.[4] Moreover, because of the restoration of the charismatic gifts, the church age would not end in apostasy, but rather the church will experience a global end-times revival prior to the imminent return of Christ. This significant difference in ecclesiology and eschatology set the early Pentecostals at odds with dispensationalism. Unable to explain the theological implications of their charismatic experience through dispensational theology, Pentecostals would turn their attention to the latter rain motif to articulate their emerging distinctives.[5] This paper examines the conflict between dispensationalism and early Pentecostalism and explores how early Pentecostals found an alternative theological framework to articulate their ecclesiological and eschatological distinctives.

The Origin and Nature of Dispensationalism

Although dispensational theology is not expressly covered in the ancient creeds of the church, throughout history theologians have endeavoured to map the divine timeline marked out in Scripture.[6] Emerging as a formal comprehensive system of biblical interpretation, dispensationalism was first developed by an early nineteenth century group of theological students in the early Brethren movement in Ireland.[7] John Nelson Darby (1800-1882), a former Church of Ireland cleric, formally systemized the hermeneutical scheme and subsequently exported the highly eschatological interpretive methodology to North America during a time of heightened end-times expectations.[8] Helping to popularize Darby’s innovative exegesis, Rev. Dr. C. I. Scofield published the Scofield Reference Bible (1909) which intertwined dispensational teachings with prophetic and apocalyptic literature in the King James Version of the Bible.[9] Despite allegations regarding Scofield’s questionable financial dealings, bigamy, and falsifying a doctoral degree, he sold millions of copies and helped to firmly cement dispensational theology in the fundamentalist doctrines of early twentieth century evangelicalism.[10] For evangelicals, dispensational theology not only upheld the fundamental truths of Scripture that were under attack by the rising tide of Modernism, but also provided a fitting interpretive system to understand end times prophecy that appeared to be unfolding around them.

As a systematized concept of biblical interpretation, dispensational theology describes how God manages the affairs of humankind in specific time periods or dispensations throughout history.[11] Each dispensation is comprised of a unique governmental relationship between God and humanity and includes a particular responsibility placed upon humanity in accordance with each governing relationship. As well, each dispensation has its own requisite demands for faith and obedience according to God’s progressive revelation.[12] Beginning with creation and moving throughout history, each successive dispensational epoch is characterized by a common pattern consisting of a test of faith to determine whether people will choose to align themselves with God’s economy, followed by their inevitable failure and subsequent judgment for disobedience.

Based upon the consistent use of a normal, plain, or literal interpretation of Scripture, dispensational theology insists there are seven dispensations that can be deduced from the Scriptures.[13] The seven dispensations are as follows:

1. Innocence (between creation and the Fall, see Gen. 1:28)

2. Conscience or Moral Responsibility (between the Fall and Noah’s flood, see Gen. 3:7)

3. Human Government (from the flood to the call of Abraham, see Gen. 8:15)

4. Promise (from Abraham to Moses, see Gen. 12:1)

5. Law (from Moses to the death of Christ, see Ex. 19:1)

6. Church (from the resurrection to the present, see Acts 2:1)

7. The Kingdom or The Millennium (see Rev. 20:4).[14]

The church age, also known as the dispensation of grace, begins with the resurrection of Christ and ends with the rapture of the church, followed by a seven year tribulation period where God pours out his wrath on an unbelieving world and apostate church.[15] In addition to this complex dispensational system, there is also a clear distinction between Israel and the church.[16] Dispensational teachers have contended that, throughout history, God has pursued two separate soteriological programs, one program involving the church or the “heavenly people” and the other involving Israel or the “earthly people.”{C}[17] The church, comprised of both Jew and Gentile believers, is considered an independent program that does not advance or fulfil any of the biblical promises given to Israel. The present church age is regarded as a period in which Israel is temporarily set aside from the dispensational program, but when the church is raptured, God will then proceed with fulfilling his eschatological purposes for national Israel. The return of the Jews to Palestine in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries made many evangelicals especially receptive to the eschatological system of dispensational theology and aided in creating and sustaining an expectation that the church age was drawing to a close, the rapture was imminent, and God was about to turn his attention back to Israel.[18]

An Emerging Pentecostal Ecclesiology and Eschatology

Within this heightened eschatological context of the early twentieth century, the Pentecostal movement exploded onto the religious landscape with an emphasis on the baptism of the Holy Spirit with speaking in tongues according to the biblical pattern of the first Pentecost in the book of Acts.[19] In North America, the epicentre of the outpouring of the Holy Spirit was the Apostolic Faith Mission at Azusa Street in Los Angeles, where people from all over the world came to seek the Lord for their personal Pentecost.[20] With three services a day, seven days a week, for forty-two months, thousands of seekers received an ecstatic spiritual experience that revived their faith and transformed their lives. In addition to the baptism of the Holy Spirit, people attending services at Azusa Street also reported experiencing conversions, healings, miracles, deliverances from addictions, and exorcisms. Arising from these experiences was a revitalized ecclesial praxis that centered upon the restoration of the charismatic gifts according to the apostolic paradigm. Illustrating the significance of this apostolic restoration, Seymour proclaims, “All along the ages men have been preaching a partial Gospel…He is now bringing back the Pentecostal baptism to the church.” With optimistic certainty, Seymour adds “The Lord is restoring all the gifts to His Church” and “it is heaven below.”[21] Unlike the pessimistic views of dispensationalism, early Pentecostals believed that they were experiencing the reclamation of all that had been lost through the centuries, the recovery of the power and gifts of the Holy Spirit, and the reviving of the one true church of Christ. This new ecclesiology led Pentecostals to consider themselves, not merely another denomination, but rather a divinely initiated movement designed to restore the fullness of the Holy Spirit evidenced by miracles, healings, signs, and wonders.

In conjunction with the emerging Pentecostal ecclesiology, the restoration of the charismatic gifts also led to the development of a uniquely Pentecostal eschatology. Believing that the outpouring of the Holy Spirit was the fulfilment of Bible prophecy and signalled the arrival of the “last days,” Pentecostals were consumed with actively and urgently proclaiming the gospel prior to the imminent return of Christ.[22] This emotive end-times sentiment pervaded early Pentecostal communities and fuelled their homiletics, periodicals, and missionary endeavours. Emanating from Pentecostal pulpits, preachers urged listeners to ready themselves for Christ’s return. Early Pentecostal publications would also reverberate with the pressing message of the imminent return of Christ and the important task of witnessing to lost people before the end of the age. The impending eschaton also inspired many Pentecostals to serve on foreign mission fields with the conviction that every person must hear the gospel before Christ breaks through the clouds. Anderson states, “The significance of this teaching for Pentecostals was that their belief in the ‘soon’ coming of Christ with its impending doom for unbelievers lent urgency to the task of world evangelization.”{C}[23] Confident that the restoration of the apostolic church was a clear indicator of the shortness of time, Pentecostals made evangelism their primary concern and viewed themselves as participants in the global harvest. “This is a world-wide revival,” declares Seymour, “the last Pentecostal revival to bring our Jesus. The church is taking her last march to meet her beloved.” “We are expecting a wave of salvation go over this world…There is power in the full Gospel. Nothing can quench it.”{C}[24] Rather than the present dispensation ending in apostasy, Pentecostal expectations were charged with enthusiastic optimism that they were partners with Christ in the last days. Deeply rooted in charismatic experience, these ecclesiological and eschatological distinctives soon established themselves within the emerging Pentecostal community and became the pervading ethos that characterized the movement in its earliest years.{C}[25]

The Conflict between Dispensationalism and Pentecostal Distinctives

Conflicting with the developing ecclesiology and eschatology of the burgeoning Pentecostal movement was the prevailing dispensational doctrines dominating the current evangelical culture. Despite having an affinity with many elements of dispensational hermeneutics, the outpouring of the Holy Spirit created an obvious theological quandary for early Pentecostals.[26] Dispensational theology teaches that the Pentecostal experience of the baptism in the Holy Spirit, speaking in tongues, and the sensational or sign gifts of the Spirit were not normative for the church age, but were only intended to inaugurate the church and terminated after the apostolic period. “Tongues and the sign gifts are to cease,” states Scofield’s commentary on spiritual gifts.[27]{C} Moreover, dispensational views also stipulate that each dispensation, including the church age, concludes in human failure and apostasy, setting any conception of an end-times revival at variance with the established dispensational paradigm. As Scofield emphasizes repeatedly throughout his text notes, “the predicted future of the visible Church is apostasy”[28] and “the only remedy for apostasy is judgment” and “catastrophic destruction.”[29] He adds, “The predicted end of the testing of man under grace is the apostasy of the professing church and the resultant apocalyptic judgments.” Inherently pessimistic, dispensationalism presents a powerless church with a degenerating future. With Pentecostals enjoying the restoration of charismatic power and gifts along with increasing reports of global revival, dispensational theology became increasingly inconsistent with the Pentecostal experience. Alert to these variants, some outspoken dispensationalists judged the budding Pentecostal phenomenon as unbiblical and even sourced in the demonic; a theological wedge was widening between the two camps.[31]

Since early Pentecostalism had not formed a satisfactory explanation for their emerging distinctives, many early Pentecostal leaders tried to articulate their theological understanding by using various forms of familiar dispensational language. Evidence of these theological inconsistencies can be found scattered throughout early Pentecostal writings, highlighting the challenge Pentecostals had in defining their ecclesiology and eschatology against traditional dispensational theology. To illustrate, William Seymour comments about the restoration of Pentecost but then states that “we are living in the eventide of this dispensation.” Charles Parham borrowed much of his eschatology from dispensational theology despite the inherent conflicting ideas. Often attempting to merge the Pentecostal experience with dispensational hermeneutics, Parham teaches that the “last days” would be marked both by the restoration of the apostolic church and also by great apostasy.[34] This theological paradox continues with William Durham who also tried integrating Pentecostal restoration with dispensational theology stating, “In the end of the days the Lord has poured out His Spirit, as in the beginning of the dispensation, and has undertaken to restore to His own spiritual church all that she has lost through the failure and unbelief of man.”[35] Numerous early Pentecostal teachers employed dispensational language to describe the outpouring of the Holy Spirit despite the obvious inconsistencies. Without a suitable framework to interpret the Pentecostal outpouring of the Spirit, early Pentecostal leaders struggled to assimilate their charismatic distinctives with popular dispensationalism and began turning their attention to the latter rain motif.

The Latter Rain Motif

The concept of the latter rain motif did not originate with the birth of the Pentecostal movement, but was developed out of nineteenth century Wesleyan-Holiness teachings.[36] Nevertheless, the latter rain motif would become the prevailing theological methodology for framing the restorationist phenomena that pervaded early Pentecostal thought. Developed from a typological reading of some Scripture passages, the basis for the latter rain metaphor asserts that the chronology of the church spiritually parallels the rainfall patterns in early Palestine.[37] The term is initially found in Deuteronomy 11:10-15 where God promises the Israelites that, if they would serve him with all their heart and soul, he would give them the “early” and “latter” rain.[38] According to ancient Mediterranean agricultural customs, to produce a bountiful harvest, a farmer requires rain at two critical points in the growing cycle.[39] Following the planting, the first or “early rain” is needed to cause the seed to germinate. Additionally, just before the crop is harvested, a “latter rain” is needed so the grain will produce a high yield at harvest time. In Joel 2:23 and 28, this agricultural model is reconfigured as a prophetic metaphor to indicate the divine timeline for the outpouring of the Holy Spirit in the church age. The first outpouring of the Holy Spirit occurred on the day of Pentecost in Acts 2, symbolizing the “early rain” that gave life to the church. Between the early and latter rains was the long, arid period of Christendom’s apostasy and corruption during the Middle Ages. When the second outpouring of the Holy Spirit occurred at the dawn of the twentieth century, it was indicative of the “latter rain,” spiritually saturating the land in preparation for the great harvest of souls before the coming of the Lord. For early Pentecostals, the latter rain motif complemented their experience and affirmed the restorationist and revivalist ethos that defined the movement.[40] As opposed to dispensationalism, which rejected the possibility of an end-times outpouring of the Holy Spirit, adopting the latter rain motif provided biblical legitimacy to the emergent Pentecostal movement and affirmed the existing notion among early Pentecostals that they were part of God’s overall eschatological timetable.[41]

Embracing the latter rain motif gave the early Pentecostals a fitting theological framework to articulate their ecclesiology and eschatology. Although they never discarded the dispensational doctrines of salvation history and most elements of Bible prophecy, the latter rain motif became the primary apologetic for the Pentecostal movement and gave Pentecostal proponents a meaningful and emotive biblical apologetic to explain the restoration of the charismatic phenomenon. Reflecting on the emphasis early Pentecostals placed on the latter rain motif, Blumhofer states:

While they [early Pentecostals] unquestioningly embraced most of Darby’s view of history, early Pentecostals rejected his insistence that the “gifts” had been withdrawn. They introduced into his system their own dispensational setting where the gifts could again operate in the church. The device through which they legitimated those gifts was their teaching on the latter rain.[42]

For early Pentecostals, the adoption of the latter rain motif seemed to remedy the theological impasse with dispensationalism- at least within the Pentecostal community. By superimposing the latter rain motif onto dispensational theology, Pentecostals retained a relatively functional framework for interpreting prophecy and enjoyed biblical support for their charismatic experience. Despite the inherent inconsistencies with merging these two theologies, the pragmatism of the early Pentecostals creatively negotiated between the conflicts and charted a new theological trajectory towards the development of a uniquely Pentecostal theology.[43]

The latter rain motif quickly took root in early Pentecostal publications throughout North American and came to define the ecclesiology and eschatology of the fledgling Pentecostal movement. Many started calling the Pentecostal revival the “Latter Rain Movement” after one of Parham’s published reports describing the beginning of the outpouring of the Spirit at the turn of the century.[44] Additionally, articles began circulating with titles such as, “The Promised Latter Rain Now Being Poured Out on God’s Humble People,” and “Gracious Pentecostal Showers Continue to Fall.”[45] Around the same time, a Pentecostal periodical out of Chicago assumed the banner “Latter Rain Evangel,” emphasizing the increasing popularity of the latter rain sentiment throughout the Pentecostal movement.[46] Seymour asserts that God “gave the former rain moderately at Pentecost, and He is going to send upon us in these last days the former and latter rain” (italics mine).[47] W. C. Stevens describes Pentecost as “saturating rains” marked by “atmospheric convulsions” breaking out “here and there in identical kind in various localities.”[48] David Wesley Myland, a Canadian-born Pentecostal pastor, wrote an influential book describing the early Pentecostal movement entitled “The Latter Rain Covenant (1910).”[49] Fused with “latter rain” thematic expressions, his book relates the prevailing eschatological ethos among early Pentecostals. Believing that they were living in the final “cloudburst” of Holy Ghost power, Myland wanted everyone to get “totally soaked” by the “latter rain” which was falling so copiously from heaven.[50] Although the latter rain metaphor had its limitations, early Pentecostals used it liberally to articulate their ecclesiological and eschatological distinctives and their favourable position within God’s plan of redemption history.

Despite the early Pentecostals’ innovative synthesis of the latter rain motif with dispensational theology, the fundamentalists were not amused. Already strongly disapproving of Pentecostal devotional ethics and restorationist claims, when the Pentecostals creatively modified dispensational theology to accommodate their charismatic experiences, a deep and long-lasting wedge was placed between the two religious groups. While Pentecostals treated the dispensational interpretive framework with value and even willingly promoted the sale of the Scofield Reference Bible, the fundamentalists were staunchly opposed to the “Pentecostal distortion.”[51] Blumhofer states:

Dispensationalism, as articulated by Scofield, understood the gifts of the Spirit to have been withdrawn from the Church. Rejecting the latter rain views by which Pentecostals legitimated their place in God’s plan, dispensationalists effectively eliminated the biblical basis for Pentecostal theology; and although Pentecostals embraced most of Scofield’s ideas…they remained irrevocably distanced from fundamentalists by their teaching on the place of spiritual gifts in the contemporary church.[52]

Regardless of the opposing opinions between fundamentalists and Pentecostals, the early Pentecostals could not deny their experience. Whether their experience was accepted or rejected by fundamentalists was irrelevant; the emergence of the charismatic gifts were irrefutable proof that God was restoring his church. Driving the Pentecostal movement was not doctrines, creeds, or theological constructs, but an intense spirituality sustained by an equally intense conviction that what they were experiencing was not only biblical, but was also a prophetic fulfilment of God’s eschatological agenda.[53] Moreover, the ensuing division between fundamentalists and Pentecostals became a catalyst for furthering the development of a more defined Pentecostal ecclesiology and eschatology that went beyond the latter rain motif towards a more well-informed biblical and theological context in the following decades.[54] Although dispensational theology maintained its usage in Pentecostal circles throughout the twentieth century, the development of the latter rain motif enabled early Pentecostals to biblically support their unique distinctives in the midst of opposing theological viewpoints.

Conclusion

Within the heightened eschatological context of the early twentieth century, the Pentecostal movement burst onto the religious landscape. The emergence of the baptism of the Holy Spirit and the charismatic gifts signalled to Pentecostal believers that they were experiencing the end-times restoration of the apostolic church. Confronting the early Pentecostal movement was dispensationalism, a prevailing fundamentalist theology that conflicted with the emerging Pentecostal ecclesiological and eschatological distinctives. Dispensational hermeneutics insisted that the charismatic gifts had ceased following the apostolic age and the church age would end in apostasy prior to the return of Christ. To the early Pentecostals however, it was visibly evident that the Holy Spirit was empowering the church for a global end-times revival. Unable to explain the theological implications of their Pentecostal experience through dispensational theology, Pentecostals adopted the latter rain motif according to the prophecies in the book of Joel which anticipated a “last days” outpouring of the Holy Spirit. Believing the “early rain” to be the first Pentecost in the book of Acts, the early Pentecostals were certain they were now experiencing the “latter rain” of the Holy Spirit in preparation for a great harvest of souls prior to the imminent return of Christ. Although early Pentecostals retained most elements of dispensational theology, the latter rain motif became a dominant apologetic for the early Pentecostal movement and provided an adequate theological framework to articulate their emerging ecclesiological and eschatological distinctives. As the Pentecostal movement progressed, a more defined Pentecostal theology developed, but the latter rain motif remains an integral part of understanding early Pentecostal thought in the midst of conflicting theological opinions.

Most Talked About Today